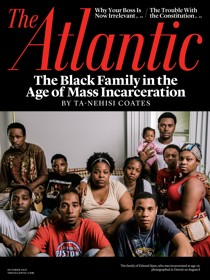

The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration

American politicians are now eager to disown a failed criminal-justice system that’s left the U.S. with the largest incarcerated population in the world. But they've failed to reckon with history. Fifty years after Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s report “The Negro Family” tragically helped create this system, it's time to reclaim his original intent.

“lower-class behavior in our cities is shaking them apart.”

By his own lights, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, was the product of a broken home and a pathological family. He was born in 1927 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but raised mostly in New York City. When Moynihan was 10 years old, his father, John, left the family, plunging it into poverty. Moynihan’s mother, Margaret, remarried, had another child, divorced, moved to Indiana to stay with relatives, then returned to New York, where she worked as a nurse. Moynihan’s childhood—a tangle of poverty, remarriage, relocation, and single motherhood—contrasted starkly with the idyllic American family life he would later extol. “My relations are obviously those of divided allegiance,” Moynihan wrote in a diary he kept during the 1950s. “Apparently I loved the old man very much yet had to take sides … choosing mom in spite of loving pop.” In the same journal, Moynihan, subjecting himself to the sort of analysis to which he would soon subject others, wrote, “Both my mother and father—They let me down badly … I find through the years this enormous emotional attachment to Father substitutes—of whom the least rejection was cause for untold agonies—the only answer is that I have repressed my feelings towards dad.”

As a teenager, Moynihan divided his time between his studies and working at the docks in Manhattan to help out his family. In 1943, he tested into the City College of New York, walking into the examination room with a longshoreman’s loading hook in his back pocket so that he would not “be mistaken for any sissy kid.” After a year at CCNY, he enlisted in the Navy, which paid for him to go to Tufts University for a bachelor’s degree. He stayed for a master’s degree and then started a doctorate program, which took him to the London School of Economics, where he did research. In 1959, Moynihan began writing for Irving Kristol’s magazine The Reporter, covering everything from organized crime to auto safety. The election of John F. Kennedy as president, in 1960, gave Moynihan a chance to put his broad curiosity to practical use; he was hired as an aide in the Department of Labor. Moynihan was, by then, an anticommunist liberal with a strong belief in the power of government to both study and solve social problems. He was also something of a scenester. His fear of being taken for a “sissy kid” had diminished. In London, he’d cultivated a love of wine, fine cheeses, tailored suits, and the mannerisms of an English aristocrat. He stood six feet five inches tall. A cultured civil servant not to the manor born, Moynihan—witty, colorful, loquacious—charmed the Washington elite, moving easily among congressional aides, politicians, and journalists. As the historian James Patterson writes in Freedom Is Not Enough, his book about Moynihan, he was possessed by 50 Years After the Moynihan Report, Examining the Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration - The Atlantic: