Education's culture of overwork is turning children and teachers into ghosts

If schools slowed down and focused on a deeper kind of flourishing, they might be more productive (if not very Goveian)

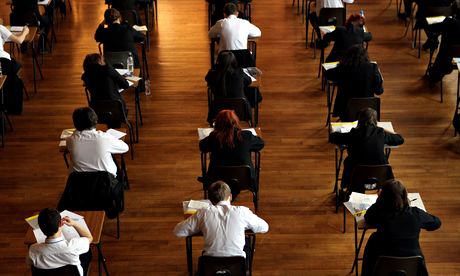

'Educational reform now largely equals intensive schooling: catch-up classes, after-school clubs, longer terms, more testing.' Photograph: David Davies/PA

Do you know a ghost child? Are you possibly raising one? A report this week by the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) pinpoints a worrying new phenomenon – the institutionalised infant, a whey-faced creature, stuck in school for 10 hours a day, the child of commuting parents possibly, wandering from playground to desk to after-school club without real purpose, nodding off through boredom and fatigue.

The sad thing is, as yet another timely ATL report brings home, the ghost child is increasingly likely to be taught by the ghost adult – a teacher grey with fatigue and stress, stuck at school for 10 hours or more a day, wandering from duty to duty in playground, classroom or after-school club. Both, it seems, are part of a culture that increasingly overworks our citizens, from a younger and younger age, in the often fruitless quest for job security and social mobility.

We know the figures. England is one of the most overworked European nations. What's really new is that we no longer question or even quarrel with this fact. Instead we deploy American-lite righteousness. Work is now not merely a sign of virtue, it is a sign of proper panic, of appropriately anxious aspiration. Any other approach takes you right down benefits street.

Such values have easily transferred to education, where decades of inequality in provision and under-investment have neatly reduced the problems in our system to one of effort, or the lack of it. When a few years ago I interviewed Sir Michael Wilshaw, then still head of Mossbourne academy, he brimmed with anger at "clockwatching" teachers whom he believed had failed to bring poorer pupils on.

Concerns like these have now morphed into a settled theory of education, and childhood itself. Educational reform now largely equals intensive schooling: early-morning catch-up classes, after-school clubs, longer terms, shorter holidays, more testing, more homework.

The trouble is, the human body and human communities do not flourish Education's culture of overwork is turning children and teachers into ghosts | Melissa Benn | Comment is free | The Guardian: